They had been shadowing me for two weeks. It was beginning to make me uneasy, even though I was ready for them.

Not that they weren’t professional about it. They worked in relays, changing vehicles and lookouts every hour or so. But after several years of this sort of thing, I was able to spot them within a few minutes.

It’s partly instinct, like knowing when someone is looking over your shoulder, but mostly it’s training, experience and years of practice. When I meet a hard-case, I know it … and start making plans.

The training was my father’s idea. He had some odd notions, noble and grand for the most part but odd nonetheless. One of his notions was to produce, in me, the “Man of To-Morrow”: a futuristic paragon of superhuman mental and physical ability who could rid the world of sickness, sorrow and evil.

To that end I was educated from my earliest awareness by a group of scientists and experts gathered by my father from around the world. I mastered arduous physical regimens ranging from gymnastics and calisthenics to acrobatics and yoga, with special emphasis on the martial arts. I studied the arts and sciences intensely until I had earned a dozen college degrees and begun instructing my former teachers. Father, a gifted neurosurgeon, personally taught me the most humanitarian science: medicine. In every conceivable way, he tried to mold me into his idealized “superman”—the Man of To-Morrow.

He failed, of course. I am as imperfect as any man. But in a way he almost succeeded—that weird training “took.”

For one thing, I am the healthiest man I know. Two hours of strenuous exercise every day for thirty-six years, along with a strict scientific diet and Spartan mental discipline, make for a sound body. And two hours of concentrated study and intense cognition each day for a like time make for a fairly sound mind.

I said “fairly sound” because, like Father, I have the obsessive compulsion that I call the “Justice Complex.” Put simply, I feel compelled to help whenever and wherever villainy threatens the lives of good, honest people. I rather enjoy the business of exacting justice—I’m a predator that preys on other predators.

The result is my peculiar “profession” of what can only be called modern-day knight-errantry.

Having made it my business to put bad-actors (and actresses) out of business, I found ample use for my father’s training. Eccentric it may have been, but it was also effective—enough so to make me highly unpopular among the criminal element.

And now, some of them were stalking me.

I was alone in my Eightieth Floor offices. My five Associates were taking a well-earned vacation from our harrowing “routine.” William Archer “Shorty” Longfellow was down in Yucatán studying the Ch’olti’-speaking Itzá Mayan tribes we’d found there. Andrus Padgett “Trog” Playfair and Theobald Harley “Sham” Cruiks had gone with him, ostensibly to enjoy roughing it in the wilderness but actually to compete in seducing the beautiful Mayan maidens. Sean “Kenny” Kenworth and Schatzi Jerome “Long Shot” Robbins were in Colorado supervising the installation of four giant hydroelectric generators on the Arizona side of Hoover Dam, with Long Shot making sure that they’d deliver power at the promised levels and Kenny making sure that the powerhouse walls and roof were bombproof.

That left me alone to mind the store.

I’d considered retreating to my Arctic laboratory/hermitage, but had decided that, with everyone else away for a while, I could do just as well here in New York. My offices were just as much a fortress and solitude is solitude, wherever you find it. With everyone else away, I saw no reason to travel halfway across the northern hemisphere for the same privacy that I already had here.

I’m going to take a moment here to correct a misapprehension that’s continued for far too long. In the popular accounts of my career in the business of righting wrongs to which I’m dedicated myself, my five Associates have been given short shrift, to the point that many consider them little more than sidekicks and hangers-on. While their excellence in their fields of expertise is generally acknowledged, it’s always implied if not stated outright that my achievements exceed theirs in those fields. While the notion that I’m more expert than these experts might appeal to the audience for these already overly glorified accounts of my activities, it’s also patently ridiculous. The whole idea of assembling a “Brain Trust” is to have a pool of expertise superior to whatever one already knows. One doesn’t consult a reference book to look up what one already knows off the top of one’s head, but to get the half-remembered details that one has forgotten or may never have learned.

In my chosen line of work, it’s often necessary to make snap decisions based on observation of phenomena and little-known facts that might apply to them. I’m admittedly very good at making associations between often arcane facts spread among disparate bodies of knowledge to arrive at conclusions that might otherwise never be forthcoming, but I certainly don’t know everything, nor could I ever remember all that I know about any given subject if I did. My Associates provide two invaluable services to me. First and foremost, they can immediately confirm or refute any supposition that I might make during the course of an investigation. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, they possess a depth of knowledge in their areas of expertise that I’ve never had time to amass and can fill me in at a moment’s notice on details of a given line of inquiry that I otherwise miss.

While I sometimes prefer to work alone and, due to my upbringing, am all too often uncommunicative when my mind is occupied, I couldn’t do what I do nearly so well were it not for my Associates and always sorely miss them whenever they’re gone.

But I digress…

It was a few minutes before midnight, Thursday, 29 June 1939. I had just completed my daily two-hour isokinetic, isometric and isotonic “dynamic tension” exercises, which pitted one set of muscles against another to the betterment of both, in seclusion of my laboratory when the “Unexpected Visitors” lamp came on.

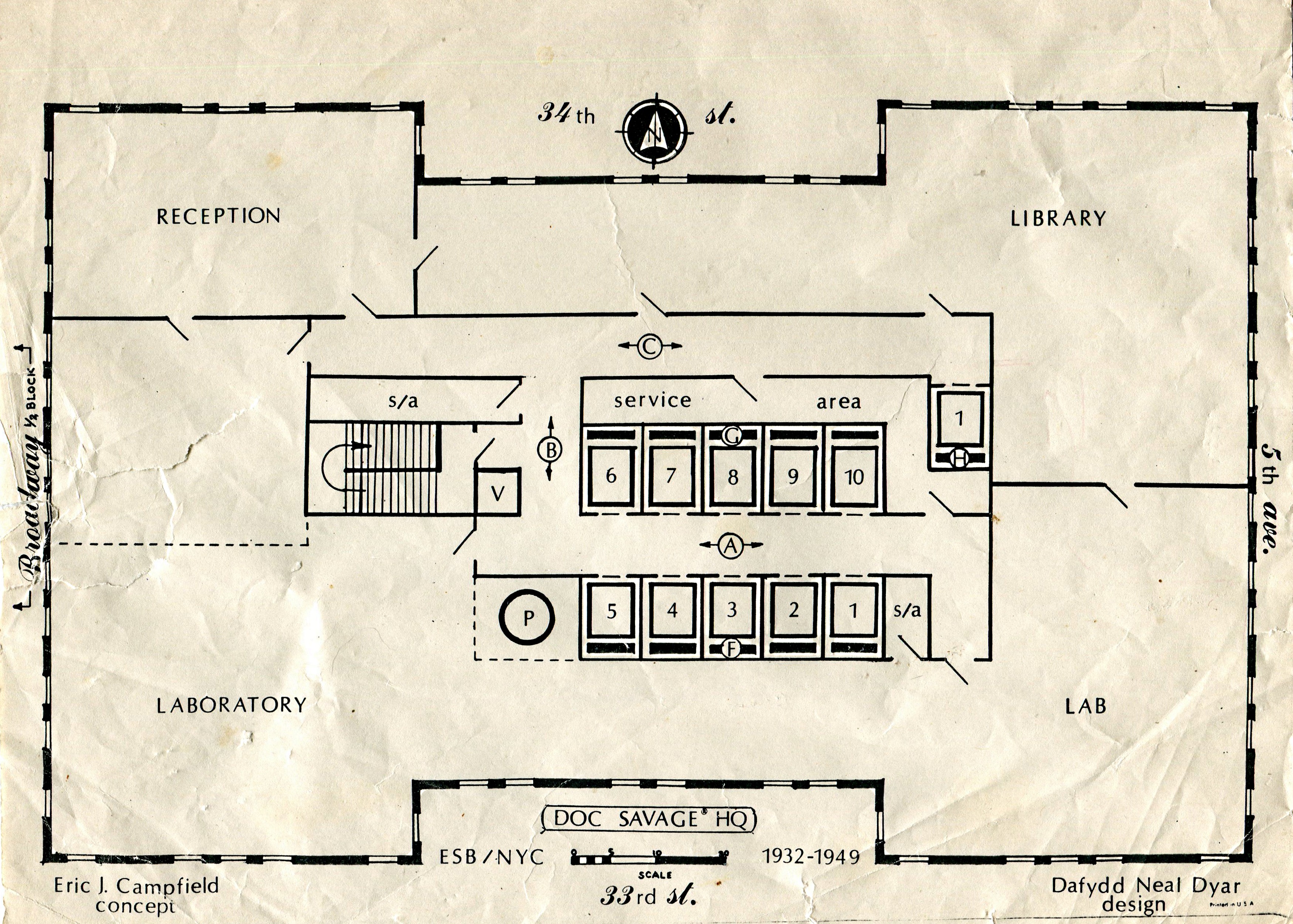

There are over seventy elevators in the building, but only six run all the way up to the Eightieth Floor. Due to engineering limitations of the cables and motors, eighty floors is the maximum distance that an elevator can travel. Five elevators stop at the central hallway of the Eightieth Floor, where passengers must cross the hall to the five elevators on the opposite side in order to continue to the Eighty-First through Eighty-Sixth Floors, the uppermost being the open-air Observation Deck. Those six floors are little more than a rectangular array of ten-by-ten cubical offices wrapped around the elevator banks and stairwell, except for the Observatory, which is simply an open terrace around the central core. As such, they are totally unsuitable for the headquarters of Hazzard & Associates. As a result, the Eightieth Floor is really the uppermost useful floor in the building. The floors above it provide few amenities other than a spectacular view.

The central hallway, with its opposed banks of elevators and the stairwell, are necessary public spaces, so they are monitored around the clock through periscopes manned by personnel in the Hazzard Investigations detective agency office on the Seventy-Ninth Floor. If they spot anyone or anything out of the ordinary, they flash an alarm to my Eightieth Floor offices and, if necessary, send armed reinforcements upstairs to help deal with any unpleasantness that might be in the offing. That was seldom if ever necessary. The timely warning that trouble was coming our way was generally all that we needed. Trouble-busting was, after all, our business.

The sixth Lobby-to-Eightieth-Floor elevator was my own personal car, located in a secluded alcove in the next hallway over from the central elevator bank. It’s an expensive necessity. It allows me and my Associates to travel unobserved and unremarked to and from our headquarters, avoiding both press and public, out of the view of friend and foe alike. It contained, among other things, radio-frequency detectors in all four corners of the ceiling. These were set up to “recognize” small transponders carried by myself, my Associates and the operator. Pressure plates in the floor of the car registered the weight of the occupants and a small computational device compared the result with the number of transponder returns divided by the average human body mass. Any discrepancy sets off an alarm and turns on the Farnsworth image dissector television camera tube in the sconce of the elevator’s Art Deco ceiling lamp.

I switched off the alarm and powered up the televisor iconoscope tube. The television system was, of course, still experimental, but quite effective for this limited purpose, so much so that I had been working on a way to replace the periscopes used to monitor the elevator banks and stairwell with television camera tubes. The problem was how to mount them in such a way that they could cover the area that needed to be watched without being seen by those being watched. It could only be resolved by developing a television system whose components were at least the same size, if not smaller, that those of the existing periscope system. So far, that was still much easier said that done.

My uninvited visitors were carrying enough firepower to tame King Kong. I took a few simple precautions, pulled on a pair of loose trousers, slippers and a quilted silk lounging robe (I had been exercising in just a pair of swimming trunks) and went into the reception room to await their arrival. I didn’t have to wait long. I had hardly sat down behind the ivory-inlaid Oriental table that I use for a desk when the tungsten-carbide steel door jumped out of its frame and toppled like a dead tree. The air rang from the muffled shock of an explosion, damped by the soundproofing insulation. The air suddenly reeked of cordite from what had to be a Kaarlo Tuurna satchel charge.

Two men stepped through the doorway, giants so alike as to give an impression of massive matched bookends. I am not a small man, myself, standing two meters and weighing one hundred and ten kilograms, but both men stood a head taller, measured a meter across the shoulders and weighed almost one hundred and fifty kilograms. They wore crew cuts and cheap suits.

Each carried a Colt M1921AC Thompson submachine gun with a 100-round drum magazine, the muzzles aimed unwaveringly at my midsection.

I slowly and carefully laid my hands out on the table in front of me with the fingers spread and leaned forward slightly. “What can I do for you gentlemen?” I asked.

A third man entered behind the twin ogres, who immediately made a flanking movement that bracketed me in a three-way crossfire. The new arrival pointed a 9mm Browning P-35 Hi-Power semiautomatic at my chest but otherwise acted very casually.

“Just relax and listen,” he said calmly. He was about forty, medium of height and build, with frosty gray eyes and mousy brown hair. He wore a stylishly tailored fawn suit that rivaled Sham for elegance and his voice was cultured and precise. His movements were fluidly economical, with the easy grace that marks years of training. He had the no-nonsense manner of the successful professional killer.

“The artillery is only to make sure you don’t try any of your fancy tricks,” said the frost-eyed man. He sat down in one of the leather-covered chairs I keep for visitors, keeping his center of mass forward and ready to move instantly should the need arise. “Once you’ve heard the score, I expect we won’t be needing weapons.”

I steepled my fingers together and waited.

He nodded appraisingly. “Yeah, you’re the cool one, alright. So let’s see just how cool you really are. I’ve got a piece of property here…”

He reached into his jacket and came out with still another weapon. This one was an antique: a .44-40 Frontier Colt Model 1873 revolver with an engraved octagonal barrel and frame, wear-worn walnut grips and a fanning spur. It had been re-chambered to fire mercy bullets.

It belonged to my cousin Cathryn.

When I looked up from the weapon, I found the three of them looking at me strangely and realized I’d been trilling again. It’s an unconscious habit I picked up while studying Zen in Tibet that I did in moments of intense mental activity. I sometimes quite literally thought out loud.

The frost-eyed man recovered his equilibrium and said, “One last demonstration.” The brass maritime clock on my desk struck eight bells of the first watch—midnight. The telephone rang.

“Answer it.” he said smugly.

“Doc?” It was Cathryn. “Doc, they got me—!”

No one could deceive me by imitating her voice. Cat, like everyone else in my family, has a distinctive vocal vibrancy or resonance. Insofar as I know, we’re the only ones who have it. My trilling is the most pronounced example of this unique vocal quality, but it was there in her clear golden contralto, albeit marred somewhat by stress.

“Hazzard!” A new voice, flat and unnaturally metallic, came on the line. “You have one hour, Hazzard. Larsen will explain my terms to you. Defy them and she will plead for death long before it finally comes to her.” Click!

“How much money do you want?” I asked grimly, returning the phone to its cradle.

“The Tick-Tock Man doesn’t want money,” said the frost-eyed Larsen. “He’s out for blood, Hazzard. Your blood.”

“‘Tick-Tock Man’?” I rolled my eyes and snorted. “With whom, exactly, am I dealing here?”

The question seemed to startle him. “You don’t know him?” He shook his head in disbelief. “He certainly knows you. He’s gone to a great deal of trouble and spent a great deal of money to take revenge. He has quite an organization working for him, of which the Twins and I are only a modest example.” He narrowed his eyes shrewdly. “Hmm. Okay, then, perhaps the name ‘Vladimir Kemidov’ will ring a bell?”

I nodded, grimly. Kemidov had been a white slaver seven years earlier. Had been, because Cat had crossed his path and put him out of business that same year. She and an archaeology professor from Marshall College named Jones had destroyed his operation and sent him to a Turkish prison a few years prior to Fathers’ death and the beginning of the Group. Cat had never mentioned it—I heard about it from Jones when we met through our mutual friend, Professor William Archer “Shorty” Longfellow. Kemidov was a genuine sadist whose method for insuring the docility of the girls he abducted was particularly revolting. The girls who survived his indoctrination were generally little more than submissive animals.

“The Tick-Tock Man sprung him last month,” said Larsen. “Should you fail to co-operate, Kemidov will get your precious Cathryn to do with however he pleases. The deal is for a straight exchange: you for her.”

He paused for effect, holstering his pistol. The Twins looked relieved.

“That holds you better than a gun would, doesn’t it?” he smirked.

“Not really,” I said, pressing one of the ivory inlays under my fingertips.

Larsen screamed as the chair in which he sat suddenly grabbed him in a viselike bear-hug.

The Twins moved faster than I had expected, but even so you could have clocked them with a calendar. I vaulted the table and swung both feet squarely into the midsection of the nearest, the ogre to my left. The other was still trying to fire his Thompson when I turned on him, as yet unaware that it was solidly jammed. Too late he tried to smash my face in with the stock.

I caught it by the stock and receiver in mid-swing, kicked him in the solar plexus and used the Thompson as a fulcrum to backflip him over my head. We hit the floor with him on his back and me kneeling on his chest. The air went out of him like a broken bagpipe.

The first Twin was staggering back up, so I clipped his temple and he went down as hard as his brother. Larsen screamed a stream of threats and curses until I put him out with a quick pressure to a cervical nerve cluster.

From a drawer in the table I removed a glass phial of cotton filters soaked in dicyclopropanol. I placed a filter apiece in each in the Twins’ nostrils. The anesthetic-soaked nose plugs were good for six hours and much more safe, effective and convenient than an injection or physical restraints.

It was over in seconds. They hadn’t had a chance.

After a decade of adventuring and attacking organized crime I had developed hundreds of techniques and methods for dealing with men like Larsen. I simply never take chances when dealing with human wolves.

I should point out here the difference between “risk” and “chance.” I will risk my life, but I will not chance it. It’s a distinction I’ve tried (and failed) to explain to Cat many times.

I had been ready for them before they had stepped off the elevator. A remotely-controlled mechanisms had sealed every entrance to and from the Eightieth Floor, dropping steel bars across the elevator doors and the threshold of the stairwell, preventing both the retreat of the uninvited visitors and the arrival of any reinforcements they might have waiting in reserve. Recording and tracing devices had tapped into all the phone lines. Even the chairs were rigged.

I had never been in danger. The moment they blew through the door, I had pressed buttons disguised as ivory inlays on the massive teak desk. A mechanism within it had emitted a coded series of ultrasonic bleeps that activated a master switcher in the next room. This had turned on the gun-jammer.

(I know it sounds like an overly-complicated arrangement, but there are over three dozen exotic devices operated from that desk. Without such a system, the desk would be a spaghettied mass of control cables weighing over a tonne. As it is, all the hardware is concealed at a discreet distance and the table appears to be nothing more than a table.)

Powerful electromagnets in the walls, floor and ceiling had jammed the guns. The induction from an oscillating high-frequency magnetic field had magnetized the ferrous alloy parts, fusing them as solidly as if welded.

An ounce of prevention is often worth several pounds of cure.

While the wolves slumbered, I took stock of the situation. I found three suitcases outside in the corridor, one each for the Thompsons and one for the satchel charge that had blown down my door. The elevator was still in place with the door open. The operator, a recent graduate of my Gifted Youngsters educational program, which provided scholarships and job placement for deserving but disadvantaged youth, was lying on the floor of the car with an expertly-broken neck.

Congratulations, genius. Damn your stupid gadgets anyway!

Her name had been Annie Bennett and she had just turned eighteen. In her locker in the 5th Floor employees’ lounge, she kept a photo of her fiancé, a Navy machinist mate only a year older. Her sightless eyes stared at me accusingly. My foresight hadn’t been enough to save her life.

Tomorrow, that elevator would be fully automatic, without a human operator, if I had to rip the old one out with my bare hands. I carried the body back into my laboratory and laid it gently on the surgical table there. I closed the accusing eyes and silently gave her a moment of my now-precious time.

I had fifty minutes in which to act if Cathryn was not also to die.

I began by getting into my “business” suit, the gear that I wear when I know that I’m going into trouble. It’s primary purpose is serve as physical protection against whatever natural or manmade dangers might come my way, but also to dish out some trouble of my own, what Trog calls “giving ’em the business!” I have yet to come up with a better name for it.

Because of my physical size and stature, every garment that I own has to be customed tailored and, since it has to be made to specification anyway, possesses some of the features of the full-up “business” suit, from lightweight flexible steel-mesh lining and useful gadgets hidden in various places, and of course I generally wear my utility vest under my (for want of better word) “civilian” suit coat and, in climates where wearing a coat would be inappropriate, under my shirt. The business suit is something special, an outfit that is as distinctive as it is practical, which I only wear when I really mean business.

From the skin out, each layer provides as much protection as possible with a little mass as possible. Everything that I wear is reinforced with tungsten-carbide steel honeycomb mesh, with three times the tensile strength of chromium steel and just as stainless, capable of deflecting an indirect hit from a modern high-velocity bullet. When multiple mesh-lined garments are layered on one another, the ensemble will stop even a direct hit, although being struck by such a bullet fired from point-blank range still feels like being hit with a sledge hammer. I don’t recommend making yourself a target no matter how well you may be armored but, if you’re going to go into the line of fire, you should be fully prepared to take a hit.

Even my “silk” swimming trunks have steel mesh sandwiched between the inner and outer layers, which aren’t actually silk. They’re made of nylon, a polyamide thermoplastic synthetic fiber first produced by Wallace Hume Carothers at the DuPont Experimental Station in 1935 and now used for surgical sutures. Stronger than whipcord but lighter than silk and completely waterproof, it may soon replace silk in parachutes. Right now, it’s still too difficult and expensive to produce in commercially feasible bulk quantities, but someday it and other manmade fabrics will replace most, if not all, materials made from natural fibers. For the time being, the rest of my undergarments—tank-top athletic undershirt, knee-length athletic socks and, when appropriate, one-piece “long john” thermal underwear—are good old American cotton and worsted wool with their own integral steel-mesh reinforcement.

At its most basic, the “business” suit is essentially an all-weather rough-and-tumble outdoor work ensemble consisting of a sturdy shirt, even sturdier trousers and boots suitable for extended hiking and climbing. The materials and design have gone through several iterations and continues to evolve as new materials become available and actual experience, both good and bad, suggests ways to improve the design.

The shirt design currently consists of a camp-collared khaki drill-cloth bush shirt with additional sleeve patch pockets on the sleeves and down the sides, with brown Bakelite snaps instead of buttons. “Snap” is something of a misnomer here, because the operation of these fasteners is completely silent, due to the fact they use rubber O-rings instead U-shaped metal springs in the cap to engage the groove in the base. Buttons get torn off and zippers jam or break at the most inconvenient time, but these silent snaps simply disengage when overstressed and work as well as ever when refastened. I use the cartridge loops above the upper left patch pocket for a set of leakproof stainless-steel pens with tiny ball bearings in place of the traditional nib, each charged with a different color ink, at least one of which is invisible to the naked eye but fluoresces under ultraviolet light.

The trousers are brown worsted whipcord “cargo” pants, which have snap-fastened pockets on the thighs and calves as well as the four standard side and back pockets, similar to those first worn by British military personnel in 1938. The current trouser design also has rubber-backed bronze-leather patches sewn over the knees and a reinforced seat, the need for which was recently underscored by a series of unfortunately events, the details of which are best left unspoken, even at the risk of leaving them entirely to the imagination of the thoroughly undisciplined mind.

Although the trousers have an elastic waist the eliminates the need of a belt, they still have one because a belt is a handy place to store small fiddly items that might get lost in a pocket and a meter-long strip of leather with substantial pieces of metal at either end can sometimes come in handy in its own right. This particular belt was made of bronze-leather, which has the virtue of being waterproof, fireproof and pH neutral and which I've further treated to make it electrically nonconductive. It’s five centimeters wide, a meter long and half a centimeter thick, with a score of loops like those on a Wild West gunbelt, into which small but useful items may be inserted at will, interspersed with grommets to which additional items, including small pouches, may be attached or removed on an ad hoc basis.

The nickel-bronze buckle and matching tongue on the opposite end are of the new quick-release tongue-and-latch “safety” type recently developed for aviation seat belts, which can be easily opened and closed securely with one hand and can survive abuse that the wearer most likely would not. Since the release slide levers are on the upper and lower sides of the buckle, the face is an unbroken polished nickel-bronze surface five centimeters square, to which I've somewhat self-indulgently affixed an enameled bronze heraldic badge of the Hazzard family coat of arms.

The boot design is based on the 1918 Trench Boot commissioned by General Pershing toward the end of the Great War, with the tops extended to cover the calf to obviate the need for puttees. Made from the same bronze-leather as the belt and knee pads, they’re fastened with interlocking hinged latches like those used on rain boots instead of laces or zippers. Like snaps, these latches they can’t come off or jam and, like the newfangled buckle, can be easily opened and closed securely with one hand. The boot toes and heels are reinforced with steel caps and cushioned with the same highly durable rubber used for the soles, which are two centimeters thick and have a high-relief tread pattern modeled on that of a tractor tire. Trog calls them “waffle-stompers” because they leave footprints that resemble Belgian waffles.

The key component of the business suit is an item that I also always wear under my everyday clothes: the utility vest. It’s my portable toolbox, medical kit, survival pack and, to some extent, arsenal. Each pocket of the vest, some of them well hidden, contained something nifty or nasty, depending on which end of them you were on. It’s made entirely of basket-woven 8-ounce 1050-denier high-tenacity nylon but, unlike the swimming trunks, hasn’t been dyed to the opacity and color of silk. Held up to the light, it appears to be a translucent nacreous silvery gray but, when worn, it takes on some of the color of whatever it’s worn over, albeit significantly paler. I generally wear it over my shirt if I’m wearing a jacket that I don’t expect to remove and under my shirt when I’m not. Of course, when I “mean business” and expect to be deploying the tools of my trade, I wear it openly over the shirt.

On those occasions when I wear the vest clandestinely, the garments that I wear over it have strategically placed slits on the sides that allow me to reach through those garments with either hand. The slits generally run along the outside edges of one or more of the patch pockets on that garment, be it a shirt or coat, and I sometimes have to reach through both a coat and a shirt to retrieve items in the vest. For that reason, every item stowed in the vest must be arranged so that I can find it immediately without having to look or search for it. Fortunately, I have both an eidetic memory and a well-developed and purposefully Braille-sensitized sense of touch. I think that it’s worth noting at this point that the utility vest does not contain anything resembling a holster or ammo magazine and the only knife that I ever carry is a Victorinox-Wenger Swiss Army “Explorer” 16-function pocket knife.

Because I am first and foremost a surgeon, I must always take care to protect my hands. While I prefer subduing opponents by pinching a nerve here and there to induce temporary paralysis or rendering them unconscious with a “sleeper” hold, I find myself having to resort to brute force more often than I’d prefer. To that end, I wear lightweight gloves similar to those worn by professional motorists and golfers. Mine are made from the same bronze-leather as the boots and have rubber reinforced palms for better grip and hemispherical nickel-bronze caps over the knuckles. They’re light enough that I hardly know that I’m wearing them, but strong enough that I can climb up to the roof of a skyscraper, slide back down to street level on a guy wire and punch through a solid oak door panel, all without injury of any kind. Scientifically-placed voids on the fingertips preclude them from impairing my aforementioned heightened sense of touch.

Because they tend to block my peripheral vision, I seldom if ever wear a hat but, just as I always have steel-mesh reinforcement sewn into my everyday clothes, I always wear a tungsten-carbide steel skullcap cushioned with vulcanized rubber. Its outline conforms exactly to my natural hairline, allowing it to be worn indetectably beneath a high-quality hair piece made from clippings of my own hair. Even in close-up photographs, it’s impossible to tell whether or not I’m wearing it unless you know exactly where and how to look. In any case, the skullcap alone isn’t enough when going out to face the elements and whatever else fickle Fate might throw at you, so I often top off with a bronze-leather aviator’s helmet with ear cups into which standard radio earphones may be easily connected. The goggles are attached to tracks around the ear cups and swing back to the nape when not in use. Snap fasteners provide points of attachment for a respirator mask.

That would be it if I only spent my time in shirtsleeves environments or in the tropics, but I also travel to arctic climes and face inclement weather everywhere I go. I have a variety of overgarments that are similarly equipped with multiple pockets and steel-mesh reinforcement, but the one that has become something of a signature is what Trog calls my “Battle Dress” jacket. It’s essentially a cropped trench coat with a double row of closely-spaced snaps in place of widely-spaced buttons, made of the same bronze-leather as the boots. The waist belt is fastened with a two-centimeter-square tongue-and-latch buckle embossed with the Hazzard & Associates corporate logo.

Among the jacket’s unique features are a wide flaring storm collar that closes up into a snug upright Mandarin collar, snap-fastened breast and side pockets and smaller pockets in the sleeves, rubberized elbow pads and a waterproof hood stowed in back pouch. The jacket is light enough to be worn as-is in climates ranging from subtropical to temperate. For colder climates, I have snap-in insulated liners of varying densities for both the shell and the collapsible hood of the jacket as well as for the cargo pants that extend the range of the business suit into subarctic regions and mountain tops. Beyond that, I must relucatantly switch to a parka or other specialized outer garments.

I have of late been thinking of redesigning the business suit yet again to make it suitable for any place on Earth to which I might venture, but that I sincerely doubt that such a thing is even possible. Still, you never really know until you try, so why not try? I’ve encountered some very strange things in my time. And, even if I don’t succeed, I may develop something else equally useful somewhere along the way. The most interesting finds are those things that you never even suspected might exist, much less spent any time actively seeking.

But, again, I digress…

Although the business suit was designed solely with functionality and practicality in mind, even I have to admit that it has a certain “daredevil” style and panache to it. I don’t know whether to be flattered or annoyed but, since I first began wearing the jacket, “knockoff” imitations of varying quality have become popular with both aviators and motorcyclists.

After donning my business suit, I also did something else that I rarely do: I armed myself with a SCAMP and several ammunition clips, which I stowed in the thigh pockets of my cargo pants.

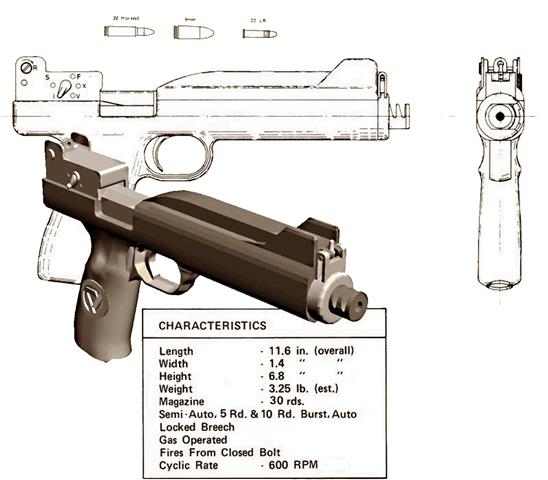

The Super Compact Automatic Machine Pistol or SCAMP is my own invention: a recoilless automatic handgun firing .22 Hornet Long Rifle cartridges at ten rounds per second or 600 rounds per minute from a 30-round magazine. It featured a five-position selective fire lever that toggled from “S” (safety) to “I” (single-shot) to “V” (five rounds in a half-second burst) to “X” (ten rounds in a one-second burst) to “F” (fully automatic: all 30 rounds in a three-second burst). The spring tension doubled at each detent, making it extremely difficult to engage Full Auto. The weapon’s frame is machined from a single solid block of duralumin, so while it’s only slightly larger in every dimension than an Army M1911A1 Colt .45 ACP semiautomatic, it’s actually lighter and easier to carry.

It’s the “mercy bullets” that make the SCAMP something more than a horrific killing machine. These liquid-filled Plexiglas bullets, resembling gelatin medicine capsules, contain a half-cc of dimethylsulfoxide and dicyclopropanol. Friction and impact disintegrate the capsule and the high velocity drives the compound through clothing into the skin. The drugs penetrates skin by osmosis and enters the bloodstream almost instantly. The target is rendered unconscious just as quickly.

Alternate loads, used only in particularly bad situations, contain cyclopropane or carbon-sulfide gas, traceable fluorescent dye, thermite or even trinitrotoluene.

Normally I don’t carry a firearm—I prefer to rely on my skill and training rather than an artifact that I can lose or have taken away from me. On those rare occasions when I do use one, I generally limit myself to mercy bullets or anesthetic gas pellets.

This time, I took one of everything.

Despite all of the lightweight materials, all that gear weighs in at around twenty kilograms, but the mass is evenly distributed, so it only slows me down a second or so, without throwing me off balance. It can quickly turn into a seriously liability, though—fall into deep water and you’ll sink like a ton of lead. That’s one the reasons that all of the fastenings on the business suit are quick-release buckles, latches and snaps. If worse comes to worst, I can shed the lot in a fraction of the time that it takes to put it on.

Still, carrying all that extra mass in concealed steel-mesh armor is well worth the effort when you expect to go up against modern high-powered weapons and potentially lethal forces that you may not fully comprehend. I’ve withstood .50 machinegun fire, grenades and small bombs in my business suit and once even tackled a small dinosaur—

But, yet again, I digress…

I checked the phone tracer and made a discovery that set me trilling again.

Returning to the reception room, I revived Larsen by releasing the nerve block and applying pressure to the trigeminal nerve. It was more effective than smelling salts and, though the sensation is like an explosion in the sinuses, less harmful than a tweaked nose.

So far, I’d been reacting, not acting. It was high time that I took the initiative.

“Larsen, you made a very bad mistake,” I said quietly. “You should have known better than to try and take me on in the first place, but you should never have killed that girl.”

“You only have forty-five minutes before Kemidov starts to work on your cousin,” he replied evenly. “Don’t think you can get away with this. You haven’t got the time, and I don’t break that easily.”

“Wrong again,” I smiled amiably. “The very fact that your friends don’t plan to kill her immediately gives me all the time I need. Unlike you, Cat is genuinely tough. She’ll hold out until I can get to her. You see, I know where she is.”

He didn’t seem to find this—or my smile—very reassuring.

“Besides,” I continued, “you mistake my intentions. I have no intention of ‘breaking you.’ I only intend to make sure you never hurt anyone else again. I presume that you’re familiar with my reputation for dealing with your kind.”

He nodded uncertainly. “I’ve heard that those who go up against you simply disappear and are never heard from again. You probably started that rumor yourself. I don’t bluff that easily either, Hazzard.”

“No bluff, Larsen.” I smiled, bringing out a hypodermic syringe and an ampoule of amber fluid. “You will disappear, and a killer named Larsen will never be heard from again.” I caught his eyes with my own golden ones and compelled his attention. “Are you familiar with the effects of laprotoxin?”

“No, of course not.” He eyed the ampoule nervously.

“You should be. It’s quite handy in your line of work.” I adopted a lecturing tone: “It’s a high-molecular-mass neurotoxin found in the venom of the female Latrodectus mactans or black widow spider. Laprotoxin is fifteen times as deadly as rattlesnake venom and highly neu-ro-tox-ic, which is to say it attacks the central nervous system, causing intense pain, profuse sweating, difficulty in breathing, violent convulsions and finally … death.” I began charging the syringe from the ampoule. “I’m surprised you’ve never heard of it before.”

“What are you doing?” His voice cracked, losing both its refinement and calm tone. “What d’ya think y’r gonna do?”

“I’m going to give you an intracubital injection from this syringe.” I smiled. “After that, you will indeed just”—I raised my free hand in a fist, then splayed the fingers to mime a puff of smoke—“disappear!”

He struggled wildly, but the chair held him fast. I ripped the sleeve of the fawn jacket and put the needle into the vein. He screamed and tried to tear himself away. Then he sobbed and finally he stared off into space with the blank expression of a man in twilight sleep.

The drug I’d given him works better when the subject’s mind is disorganized, and nothing disorganizes a mind like fear. And I hadn’t actually lied. Black widow venom works exactly as I’d described it and Larsen, as Larsen, would disappear. Larsen the Killer would never be heard from again.

I never kill or seriously injure anyone if I can avoid it. Once defeated my opponents, they cease to be threats to anyone else and become my patients. The mindset that allows behavior like theirs is invariably a mental disorder of one sort or another and I have a cure of sorts.

Larsen and the Twins and any of the others that came into my hands would have their memories erased in my upstate sanitarium. When their course of treatment was finished, their personalities and characters will have been rebuilt. They will have no recollection of their former lives and, thus, no criminal habits or tendencies with which to contend.

It wasn’t simply a matter of Life or Death, but a matter of Justice. Killing or imprisoning Larsen would not bring Annie Bennett back, nor lessen the grief of her passing. Why waste more lives? By restoring sanity to these men, I was making it possible for them not only to atone for their crimes, albeit they’d never know that, but to do some good with their lives as well. Larsen the Killer would be gone. He would be reborn as an altogether nobler, gentler and wiser man.

No, I hadn’t lied—I hadn’t even said that the amber fluid was spider venom. It was actually sodium amytal, a powerful barbiturate used in narcosynthesis and sometimes mistakenly called “truth serum.” I knew enough to take action at this point, but I needed to know more. Cat’s life might depend on it.

The interview that followed was disappointingly vague and shed little light on what I already knew. Larsen had no idea who the Tick-Tock Man was, knowing him only by that name or as “the Leader.” He couldn’t even give me a description—his unknown boss always wore a hooded cloak that shielded him from view. They called him the Tick-Tock Man because a clock-regular ticking sound came from his cloaked form, or possibly from the arcane machinery that always attended him. Larsen thought he might be a cripple, confined to a motorized wheelchair.

“He never leaves that chair of his, never!” he babbled. “I sometimes think he’s part of it, or it’s a part of him … he must sleep in the damned thing … if he ever sleeps…”

The Tick-Tock Man had brought over two dozen men with him: professionals like Larsen, brawn like the Twins and “specialists” like Kemidov. His base of operations was inside a large moving van, mobile and inconspicuous. Three men watched me constantly—one now watched the lobby and another the subbasement garage while a third waited outside the building’s main entrance, just in case. They would be paid $1,000 each when it was over—Larsen and Kemidov had been paid $5,000 in advance.

Cathryn had been abducted two hours earlier from the 7th Floor apartment of her Park Avenue establishment. She’d managed to mangle a few of them before they enforced her cooperation with a liberal dose of chloroform.

Cat has always been a scrapper.

“Toughest little broad I ever saw,” murmured Larsen, losing more of his refinement under the effects of the drug. “I think the only reason she finally gave in was she figured you’d be able to get her out again. She thinks you’re some kind of superman or something…”

It figured. Cathryn had a bad case of hero-worship. That, and her natural propensity for daredevil thrill-seeking—an inherent Hazzard family trait to which even I am not immune—prompted her continual contriving to be allowed an involvement with my work. Now she was involved up to her pretty little neck again … and, once again, it was up to me to save it for her.

The maritime clock struck the first bell of the mid-watch—12:30 a.m. Grilling Larsen had used half my time allotment.

At least I knew where to find her. If the Tick-Tock Man had been able to resist that gloating phone call, he might’ve had me. Narcosynthesis is unreliable and Larsen might not have talked. But call he had and now I had him—if I could just move fast enough and take him by surprise.

I had known that Cat was being held somewhere nearby the moment I’d answered the phone. An out-of-town call would have been prefaced by an operator and the one-hour deadline for the exchange put us within thirty miles of each other. That proximity had freed me to act, knowing that Cat was within range of the automatic phone tracer. I just hadn’t known how close.

They were only seven blocks away, in my own hangar/boathouse on Pier Seventy-Four overlooking the Hudson River. The implication was disturbing—this Tick-Tock Man knew far too many of my secrets.

My “profession” requires ready access to means of long-range transportation, but also necessitates a low profile, so the advanced air and sea craft that I use are stored in a “warehouse” of the fictitious Yucatán Trading Company on Pier Seventy-Four. Myself, my five Associates, Cat, Mayor LaGuardia and Governor Lehman (who had signed the permits) should’ve been the only ones who knew of the arrangement. The building was bombproof, fireproof, soundproof and scientifically guarded.

Yet my unknown enemy not only known about it, he’d known how to circumvent the radio-controlled electromagnetic locking devices. He had occupied the most highly-fortified building in Manhattan and turned it against me.

Chalk up one for the Tick-Tock Man, whoever he was.

I was now faced with the task of breaching my own defenses, against a man who apparently knew them as well as I did, without tipping him off as to what I was doing—and doing it all within half an hour. Only one man had ever put me in such a position before, but he was dead now.

Or was he?

I dosed Larsen with a pair of anesthetic nose plugs and went to the laboratory. The clock seemed to tick loudly, but it was only my pulse. I collected a device resembling two canister-type vacuum cleaners welded together and a parachute harness from the storage lockers in the lab and carried them up around to the west end of the Eightieth Floor, to my private apartment midway between the lab and reception room. In the ceiling was a reinforced steel trap door that swung down and unfolded into a step ladder leading upward to one of the two terraces around the Eighty-First Floor. It was also a portion of the roof of the Eightieth Floor not occupied by the top six floors.

The Empire State Building, like most skyscrapers, is essentially a vertically elongated ziggurat or stepped pyramid. Even though new steel alloys are constantly being developed and refined, none are strong enough so support of the weight of building from foundation to rooftop in a single continuous vertical span. The solution to this physical limitation is to build in a series of successive spans, each of lesser area and mass than the one below, like a child's building blocks. The setbacks thus formed naturally lend themselves to use as balconies, decks, patios, terraces and verandas. The Empire State Building is divided into seven distinct blocks: the First Floor, the Second to Fifth Floors, Sixth to Twentieth, Twenty-First to Twenty-Fourth, Twenty-Fifth to Twenty-Ninth, Thirtieth to Fifty-Fourth, Fifty-Fifth to Seventy-First, Seventy-Second to Eightieth, Eighty-First to Eighty-Fourth and Eight-Fifth to Eighty-Sixth, which is topped by the distinctive stainless steel spire that raises the building’s overall height to One-Hundred-Two stories.

Of the nine setback “rooftops” thus created, only two are actually habitable: the 360° panoramic terrace around the Eighty-Floor Observatory that serves as the Observation Deck and the East and West Terraces, more accurately described as balconies, that bracket the Eighty-First Floor. These two terraces are not open to general public, their use being reserved for building occupants, residents, authorized special guests and those ready, willing and able to pay for the privilege of enjoying the spectacular view that attends standing out in the open air two-hundred and sixty-five meters up. There is another ceiling hatch on the east side of the Eightieth Floor, between the library and laboratory, that allows access to the East Terrace. For my purposes, only the West Terrace would do.

The lobby, garage and main entrance were under surveillance. The passenger pneumatic-tube car that shuttles between my Eightieth Floor laboratory to the waterfront “warehouse” seven blocks due west was known to the enemy and would be both monitored and guarded. Even if it were still a secret from them, they’d hear the tube car coming into the warehouse terminus long before it arrived. (Soundproofing can only do so much. The sound vibrations have to go somewhere. In this case, they were literally piped into the Hudson River, where waterfront noises drowned them out insofar anyone outside the warehouse was concerned, but it still sounded like an oncoming freight train to anyone inside the warehouse.)

There was only one route left open to me.

I’d have to fly over.

The wind ripped past me like a vertical gale as I stepped out onto the West Terrace. Three hundred meters below, the streets of Manhattan spread out in a sparkling grid of lights. Above was an unrelieved mass of blackness broken only by the brightly-lit pillar of the spire, mounted atop the Observatory six floors above and extending from another sixteen, where it was topped by an enclosed observatory dome at the pinnacle. The mass of the city-block-spanning building deflects the prevailing into a powerful updraft, making the shining steel spire, originally intended to serve as a dirigible mooring mast, useless for anything more than an Art Deco ornament suitable for postcards.

It was a disturbing reminder than even the best of plans can fail due to unforeseen circumstances.

I removed a small packet from the left side pocket of my jacket. It contained nine pairs of colored lens, one pair for each of the seven pure colors of the spectrum, plus the infra-red and ultra-violet. You’d be surprised by you learn when you view even the most everyday items through such monochromatic filters, especially at the far ends of the spectrum. I snapped the pair of infra-red filters onto the lenses of my aviation goggles, stowed the packet back into its pocket and prepared to risk both my own life and Cat’s on yet another unproven gadget. The goggles turned the array of lights into a starkly defined black-and-white view. Then I carefully inspected the Cirrus X-3 Mark II experimental prototype self-contained rocket motor that I’d brought from the lab, before strapping it securely onto my back with equal care using the parachute harness.

I wasn’t the first damned fool to try this stunt, but I at least had the distinction of knowing better. I was, after all, the one who had designed the fool thing.

I had never intended for the Cirrus X-3 to be used for personal flight. But after some Nazi agents stole it from the Guggenheim Aeronautical Laboratory at the California Institute of Technology where it was being tested, it had somehow ended up in the hands of a young barnstormer who had tried imitating Daedalus with it. This “Rocketeer” had been quite a sensation for several weeks before my Associates and I finally recovered my stolen property.

Whatever else the Rocketeer may have been, he was a good pilot but, even so, he had never really mastered the rocket’s wild thrust. I had the advantage of knowing the machine inside-out, but that knowledge was of little practical value. The thing had had to be rebuilt after almost every flight. “Flying” it was difficult enough, but landing it was murder!

I switched on the internal gyroscopic stabilizer (a feature about which the Rocketeer had never had a clue) and checked the control studs on the handgrip while it came up to speed. The centripetal force began to push the motor backward and upward into the full upright position, at which point it was ready to go. I took a deep breath and jumped up onto the granite ledge that enclosed the West Terrace. The precession of the gyro lifted me faster than I expected and shoved me over the edge before I was ready. I arched backwards to keep my back straight and squeezed the control stud to first detent—launch thrust!

Take fifty kilos of trinitrotoluene. Put it in the bottom of a bucket. Upend the bucket and sit on top of it. Then detonate the TNT…

A wash of blast-furnace heat swept across the backs of my legs as I shot upward like a humanoid comet. I lost control almost immediately, spun crazily on all three axes, nearly smashing into the mast. I missed it by about fifteen centimeters and veered out into the empty darkness of the night sky.

It was a Hell of a long way down to the ground.

I regained control by spreading my arms and legs and jack-knifing, then straightening out and bringing my legs together behind me and my arms together above my head, as if performing a high dive, which in fact I was, albeit in a power dive. The moment I felt that I was actually in control, I cork-screwed to the side away from the building so that I banked sharply around the Observation Deck. That dive cost me about two hundred meters in altitude, but that last maneuver had gotten me into more-or-less level flight.

Assuming the neutral free-fall position, I finally oriented myself and began what can best described as a sideways dive. I careened outward in a high arc over Sixth Avenue and shot past the twenty-five-story Hotel McAlpin and the ten-story Gimbels, five-story Saks Thirty-Fourth Street and ten-story Macy’s department stores in Harold Square loomed up ahead like the straits of Gibraltar—I flashed between them at over ninety kilometers per hour.

I hit a crosswind and started to swerve as I swept past the twenty-two story Hotel Pennsylvania, causing me to graze against the Thirty-Third Street side of Pennsylvania Station with a screech like a wounded banshee. The rocket’s stabilizer fins sheered off, leaving a trail of incandescent sparks until I ricocheted off the face of the building, tumbling and side-slipping out of control. My heart clenched like a fist as I switched off the gyro and used body English and main strength to twist through a one-and-a-half gainer with a double back somersault. I recovered just in time to avoid splattering myself against the Nelson Tower and shot back up like a misguided meteor into clear air and relative safety. Even so, my hand trembled slightly as I squeezed the stud to second detent—half-thrust.

It was literally all downhill from there…

I spread my arms and legs wide as I arced over the forty-three-story Hotel New Yorker and dropped into a gently sloping glide worthy of a flying squirrel past the fourteen-story Sloane House YMCA. Below were the tracks of the Pennsylvania Station Railway Yard. Up ahead I could now just make out the squat silhouette of the Yucatán Trading Company. Seven stories high and a block long on a side makes a fairly easy target, but I still came close to overshooting it. There was nothing one the other side but a twenty-meter drop into the Hudson.

I pulled my knees up in a tuck-and-roll and boosted the rocket back up to full-thrust to kill my airspeed. As the roof roared away beneath me like the deck of an aircraft carrier, I kicked in the gyroscopic compensator for all it was worth and again threw myself wide open to bleed off the remaining airspeed. I hit the roof at twenty-five knots, scraping one boot heel down to the shank as it took the brunt of impact. I spun like a top, leaving a black ski dmark that looked like a child’s drawing of spaghetti before going head over heels across the concrete roof.

Only years of honing my reflexes and practical experience with parachutes saved me from serious injury. I rolled bonelessly as I hit, taking the jolt along my back. The rocket was reduced to flaming scrap as it took the brunt of the impact, leaving me with a massive bruise between my scapulae and knocking the wind out of me. Except for a few minor “road rash” abrasions, it was essentially a pratfall.

Fortunately, that final braking boost had expended the last of the rocket propellant…

Getting out of the harness was not unlike escaping from a straitjacket. It took time—precious time that Cat and I could not afford. My Longines Lindbergh Hour Angle aeronautic chronograph had rapped smartly against the roof at one point and was now frozen at 12:40, twenty minutes to deadline.

I’d been stunned in the crash landing and was unsure of exactly how much time I’d spent sprawled on the roof or digging out of the harness. I limped across the roof to the nearest ventilator intake and began the tricky job of removing the booby-trapped cover.

The rooftop ventilation intake were hidden beneath was was ostensibly a billboard laid across a section of the roof for the edification of those flying over lower Manhattan:

In the ancient Mesoamerican reckoning, this corresponded to the Gregorian calendar date Saturday, September 24th, 1932—the date the incorporation papers for the Yucatán Trading Company became effective. In order to operate the combination, one not only had to know this particular date, but also how to convert it into the Mesoamerican date reckoning system and find all of the corresponding glyphs on the face of the graphical representation of that calendar. The schematics of the building stored in my Arctic refuge wouldn't contain any of that critical knowledge except the Gregorian date.

The cover unlocked, after which it was simple enough to swing the billboard up on the concealed hinge running the length of one side and swing it up and over, but this hidden cover was only the first line of defense. The ventilator screens, like all possible entries to the building, were charged with a high-frequency electric current designed to stun an intruder and set off an alarm if touched. I used two insulated cables from my utility vest to connect the hidden terminals and shunt aside the current, then unbolted the screen and pulled the bolts holding the cover in place.

There are times when I regret my own thoroughness. The few minutes it took to circumvent my own defenses seemed very long indeed. But even as I ripped the screen off, I was making mental notes to eliminate this chink in my professional armor.

Some days, I wonder.

As soon as the cover slipped free, I removed a rubber-coated grapnel from my vest and attached it to a silk line. The line fed from a retractor reel like those used for surveyor’s measuring chains, with a pressure-grip to control the rate of feed. I hooked the grapnel on a nearby standpipe and dropped down the shaft like a spider descending on a thread.

Light flooded in through the ground level ventilation grill. Once I had firm footing I peered through the louvers, pushing the cracked infrared goggles up to get a better view.

From my vantage point I could see most of the interior. A wide variety of sea craft were moored in docking slips: the hundred-meter fusiform of the heavily-modified O-class submarine Devilfish, my research ship The Seven Cs (six letter Cs arranged in a hexagon around a seventh C), Cat’s sloop-rigged catamaran Cat’s Meow and a twin-engine Grumman G-21A Goose flying boat known variously as Gone Goose and Taken Gander.

On a concrete pad nearby sat various aircraft: my old reliable Stinson Model A tri-motor, a Westland CL-20 autogyro and the Heston Racer speed plane, its 2200-horsepower Napier Sabre engine torn down for maintenance. The stratosphere dirigible Zephyr was tethered overhead like a captive storm cloud. Experimental craft in varying stages of completion were up on blocks. The hydrofoil speedboat Flying Fish, the Cirrus X-5 rocket-propelled flying wing Pterosaur and the submersible hovercraft Triphibian were among the most promising.

The space normally occupied by my twin-engine Lockheed Electra 12A was empty. Shorty, Trog and Sham had flown to Yucatán in it two days earlier. In its place stood the Tick-Tock Man’s mobile hideaway: a huge 1936 E Model Mack cab-over diesel moving van.

A dozen men stood around the van armed with Thompsons, M1918A2 Browning Automatic Rifles and Savage Arms Model 11 semiautomatic shotguns. Six more, unarmed except for esoteric cutlery, were grouped around a hooded and cloaked figure in a throne-like wheelchair.

Cathryn knelt at his feet, looking tired and bedraggled but defiant. Her long glossy reddish-gold hair, like spun copper, was loose and disheveled and her her only garment, a torn and rumpled satin nightgown, was soiled and bloodstained. Her wrists had been bound behind her back with several turns of barbed wire, encrusted now with dried blood.

Her captors were not without a few marks themselves. More than one was bruised or scratched or had blackened eyes or broken lips. Kemidov had his right arm in a sling. He muttered something to the cloaked figure, too softly for me to hear, and sniggered nastily.

Cat glared at him. She retained her poise and dignity, holding her head up with fearless pride. Captive as she was, bound and kneeling at her captor’s feet, she still seemed to stand a head taller than anyone else in the room.

The Tick-Tock Man spoke, his voice a toneless metallic drone with an inhuman mechanical quality to it, as if it came from a tinny old phonograph.

“Hazzard is late,” it droned. “We will delay no longer. Kemidov, the girl is yours.” A sigh shuddered from him. “I had so hoped he’d be here to watch!”

Kemidov grabbed her by the hair with his good hand and twisted her head up and back. He leered at her and snarled, “You will live a long time, koshka, but you will not enjoy it!”

Several things happened seemingly at once. Kemidov jerked sharply upright and dropped screaming on the floor. Part of the far wall exploded in a shower of sparks and the building was plunged into darkness. Some of the gunmen started firing blindly amid the babel of orders, questions, exclamations and expletives.

A moment earlier I had drawn my SCAMP and charged it with cupronickel-jacketed tungsten carbide armor-piercing rounds. Then I had braced my shoulders against the walls of the shaft and my feet against the vent grill. Aiming through the louvers was like trying to shoot through a Venetian blind and the infra-red filtered goggles didn’t help, but I needed to keep them on in order to see the unique heat signature of my target.

Whenever I’d used the SCAMP at all, I’d previously locked it into the single-shot semiautomatic mode and made every shot count, but under these circumstances I thought it wiser to use the 10-round burst mode. I aimed for the center of the electrical junction box on the far wall, fired a single one-second burst, then immediately contracted the muscles from my shoulders to my feet in one continuous surge and the grill popped out of its frame with me right behind it. Most of the copper-jacketed slugs made Swiss cheese out of the junction box, creating at least half a dozen short circuits that killed the lights and plunged the interior of the building into total darkness. Kemidov had been standing just off to one side and had taken one through the shoulder of the arm not in a sling.

Sometimes, Justice and Luck can both be blind at the same time.

I landed running and sprinted across the hangar at top speed, picking Cathryn up onto one shoulder. I overturned the wheelchair with the other, sending its cloaked and shrouded unknown occupant sprawling down onto the floor.

We made the far wall while our opponents were still a confused mob. The still-hot filaments of the overhead lights put out nearly as much illumination as before when viewed by infra-red, but to everyone else it was in pitch blackness.

“Hold your breath!” I warned Cat in Ch’olti’, an obscure Mayan dialect that my Associates and I used for secret communications. Cat had learned it from Trog and Sham. I started lobbing cyclopropane gas grenades into the mob as I spoke and the gas quickly filled the hangar like a heavy white fog. I fished a respirator mask out of my vest and pressed it to her face. In her weakened condition, she probably couldn’t hold her breath for long.

One by one the men collapsed like deflated balloons. After about three minutes the cyclopropane anesthetic oxidized and lost its effect. I waited five minutes to be safe, then opened the hangar doors to flush out any remaining gas.

“Doc!” yelled Cathryn, muffled by the mask. “Where are you?”

“Right here.” I replied, removing the mask and standing her on her feet. “Just a minute while I fix the lights.” I set her down in the Tick-Tock Man’s wheelchair, then crossed the hangar, disconnected the power mains, performed a minor bypass operation on the junction box to restore as many of the circuits as possible, reconnected the mains and reset the circuit breaker. Most of the lights flooded back on.

“So,” grated a metallic voice behind me, “now it’s down to just we two.”

The Tick-Tock Man stood next to Cat with a hand around her throat. His cloak had come off or been discarded and he wore an ensemble of all-black clothing: a cloth coverall garment and a breastplate, gloves and boots of molded leather. His right arm was supported by a steel brace. A clock-like ticking came from somewhere inside him. His face was terribly scarred but still recognizable.

His name was Shawn Twilight.

Eighteen months earlier, I had looked on helplessly as a mob of Göktürk, Karluk, Kashmiri and Uighur Soyombo Yekhe Khagan religious fanatics in the Karakoram had fervently hacked Twilight to pieces with kilij sabers. He had been posing as the Devil Temujin and I had exposed him. Two months before that, he had stolen a number of secret devices from my Arctic laboratory. He was the most dangerous man I’d ever known and now he was back, quite literally with a vengeance.

“Surprised, Hazzard?” he droned, and this time I noticed that his mouth didn’t move. The voice came from a box strapped to his chest, with a wire running from it to the flexible steel cable contrivance that now constituted his neck: a Voder Voice Operating Demonstrator speech synthesizer.

“Throw away all your weapons and gadgetry … or the girl dies now!” he grated. Cat’s sudden yelp of pain underscored the threat.

I tossed the SCAMP over my shoulder, then quickly stripped off the jacket, utility vest, goggled helmet, gloves, boots and cargo pants—anything and everything with pockets or could be classified as a “gadget”—tossing each item over my shoulder, well away and behind me. After a moment, I stripped off my socks as well—the mesh reinforcement wouldn’t protect my feet enough to offset the loss of traction inherent in stocking feet. I now faced down the resurrected Shane Twilight in just my swimming trucks and undershirt, barefoot and empty-handed.

Sometimes, that is more than enough.

He smiled with only one side of his mouth and released Cathryn. He still had the face of a haunted poet, marred now by polished stainless steel teeth and what appeared to be a Leica F 35mm wide-angle rangefinder camera lens in a telemeter coupling M39 LTM aluminum mount in place of the left eye. He pulled off his gloves to reveal one long-fingered human hand and one of stainless steel. The left hand was a skeletal contrivance of rods and cables connected by a U-joint to a slotted steel “forearm.” His entire left arm was a mechanical pantograph.

“I am going to kill you with my bare hands, Hazzard.” He stepped forward: whir-click! Another step: whir-click! Both legs were also artificial constructs, like the arm. He flexed them, demonstrated their smooth mechanical action and made a sound that started out as something akin to laughter but ended as a feral growl, all of it distorted by the tinny buzz of the Voder. Then he attacked.

Had he been a trained fighter, I would have died there and then. His speed and strength were literally inhuman. I avoided his blows only because he telegraphed his moves. The steel arm scythed past my head and ripped a scar in the concrete wall behind me. I ducked under it and drove a fist into his kidney region. My knuckles rapped smartly off what appeared to be a hydrogen fuel cell buried in his left hip.

The arm snapped back and almost clipped my shoulder. The steel-braced human arm smashed hard across my face. Only that brace gave it any impact—the arm itself was emaciated to the power be almost useless without its hydraulically-assisted bracing. Head reeling, I kicked at his solar plexus only to be foiled by the leather breastplate.

I had to find some part of him that wasn’t mechanical or armored … and find it fast!

The mechanized steel arm sliced past my head again with the steel-braced human arm close behind it. It was as well that he wasn’t using his feet! Maybe he couldn’t? I snapped a kick into one kneecap without noticeable effect and then jumped back to avoid his steel-braced elbow.

Something exploded behind my eyes and the lights dimmed—

The steel arm had moved with blinding speed and clipped me across the temple. Only the bulletproof skullcap had kept my head from being caved in. It knocked me sprawling, stunned. Twilight moved in for the kill like a mechanized Grim Reaper.

“Die!” he whined. “Die as I would have died, hacked into a thousand parts!” The sound of clockwork filled the air as his shadow fell across me.

With a Valkyrie battle cry, Cathryn launched herself at him feet first, landing both of her bare feet in his face in a flying side kick. The blow unbalanced him for a moment, but he recovered and backhanded Cat in midair with his braced arm. She went down hard, fresh blood appearing on the wire binding her wrists.

I came off the floor just as Twilight’s fist came down like a pole axe, shattering concrete where my chest had been. I chopped him across the neck at the juncture of the jawbone and ear, which seemed to stun him briefly.

Cathryn had shown me his weakness even as she had saved my life. His replacement mechanical parts might indeed be invulnerable, but the original flesh-and-blood body parts were not.

I snagged his weak, steel-braced human wrist and jerked forward, twisting it to expose the elbow. Jabbing the heel of my other hand just above the elbow joint, I twisted the arm up behind him, jerking the wrist up to lock it into the small of the back. Then I grabbed the steel collar and reared back. My muscles screamed and my joints crackled as I levered him over my head and threw him up, up and away.

The Voder emitted a high-pitched squeal as his body arced through the air. He landed in the mooring slip of the Cat’s Meow with a tremendous splash. Then came a blinding flash of white glare, a fountain of salt water and the sharp smell of ozone.

Whatever else it may have been, Twilight’s mechanical body parts weren’t waterproof. Some of them shorted in a shower of sparks and ignited something, probably hydrogen leaking from the fuel-cell, which exploded like a small bomb.

I helped Cathryn back into the wheelchair after clipping the wire from her wrists and removing it as gently as possible. I procured bandages, antiseptic and benzocaine from a wall locker and treated the wounds, taping them for extra support. I’d get to Kemidov in due course. Cathryn kept up a running monologue throughout the operation.

“Doc, I thought you’d never get here!” she rattled breathlessly. “That … thing … was planning to do all manner of outrageous things to me to get back at you for something. Who was he? For that matter, what was he? I thought he was a helpless cripple until the lights came on and he put his … claw around my throat!” She shuddered. “Y’know, if I didn’t love you so much I’d be kind of mad about this. I mean, he’s your enemy, not mine, so he should pick on you, right?”

“Anyway,” she went on, “there’s an arsenal in that truck, and radio gear and Lord knows what else … some kind of color television projector that produces life-sized solid-looking images … the Tick-Tock Man used it to report to the man who rebuilt him … a bald-headed green-eyed Chinaman who’s a ringer for that ‘Ming the Merciless’ character in Flash Gordon but without the goofy beard … they got into a big argument about something but I don't know what because they were speaking Chinese…” She stopped, out of breath.

“Let’s get you home, shall we?” I said, crushing an anesthetic capsule that I had palmed in my hand. “I’ll bet you’re feeling sleepy right now.”

She blinked groggily. “I guess I am at that.” she muttered vaguely. “But you owe me one for this, Doc Hazzard—” Her voice trailed off and she keeled over. I wrapped Twilight’s cloak around her and picked her up gently.

“Later.” I whispered. “Little girl, you’ve had a busy day!”

It’s been a year now, but Cathryn still hasn’t forgiven me for that trick. The fact that she was emotionally and physically exhausted while mentally supercharged from adrenaline cuts no ice with her. I guess I should be happy she’s so resilient—to look at her you would never know it had ever happened. The only scars are the ones on her wrists, and you have to look hard to find those.

She still tries to get involved in my work.

Larsen, the Twins, Kemidov and the rest of Twilight’s men “graduated” from the Phoenix Foundation “Adirondacks Wilderness Cure Cottages & Sanatorium” six months ago and now they really are literally new men. Larsen works as a charter pilot flying medicine and supplies to remote sites in the Andes. Kemidov is a physical therapist and masseur in Cat’s Park Avenue salon. The Twins work for me at the Trading Company as mechanics.

An autopsy on Twilight showed that he was in fact more machine than man. Half of his internal organs had been replaced. His lungs were completely mechanical, which explains his immunity to gas. His heart had never been very human even before it was replaced with a rotary pump. I’ve duplicated and patented several of the devices that I found in him—the perfusion motor is now being used in hospitals across the country—but, despite my best efforts, I have been unable to determine the actual purpose of others, much less how they function. I especially wish that I could work out the principle behind that stereoscopic projector—now that gadget is a genuine marvel! I must admit to more than a little jealousy of the intellect that it took to design and build it.

But as I learn more about how it was done, I keep coming back to the nagging question of who could have “rebuilt” Twilight … and why? The handiwork is somehow familiar to me, naggingly so. Whoever it was, we have met before. Given the nature of his latest work, I have no doubt that we will someday meet again and settle whatever differences lay between us once and for all.

The day immediately following what Cat calls “That Fateful Night”, Manhattan was abuzz about mysterious fireball that had streaked across the midnight sky and rattled the windows with its thunder. By the noon edition, the New York Times put the matter to rest with its exclusive interview with the Franco-American pyrotechnician who’d barely escaped with his life when the Fourth of July fireworks extravaganza he’d been installing in the spire of the Chrysler Building to mark the sesquicentennial of the 1789 French Revolution as well as the 163rd American Independence Day had spontaneously combusted due to nearby heat lightning. The plan to launch fireworks from a midtown skyscraper was subsequently scrapped and the venue moved to Welfare Island in the East River, where such things belong.

The story has the saving grace of being technically true. The actual incident occurred a few earlier days and only produced just enough smoke to smother the fire before it got started, serving as a “wake-up call” with regard to a folly of stockpiling such volatile materials in the heart of New York City. What came to be known as the “Midtown Manhattan Meteor” story proved to be such a good one that even those who had been involved in what Trog calls “Frenchy’s Fireworks Fizzle” took to telling and retelling it to anyone who’d listen, with the usual alcohol-fueled embellishment.

The tragic accidental death of a young woman who operated the private elevator for the celebrated doctor who famously lived and worked on the Eightieth Floor of the Empire State Building as part of a WPA-style “make-work” project was considerably less well reported, much less given any scrutiny. She deserved so much better.

In fact, the only real tragedy in the whole affair has been the senseless untimely death of Annie Bennett. I signed the death certificate myself, listing the cause of death as “accidental.” The Coroner, unfamiliar with the jiu-jutsu technique of kubi-ashi-naga, agreed that her neck must have been broken by a fall against the side of the elevator. A new, fully automatic elevator car has now been installed and I have arranged a trust fund pension for her parents, but it doesn’t seem nearly enough.

It’s never enough.

I can’t afford regrets, but I can learn from my mistakes … and make sure that I never repeat them.

“Let me strive, every moment of my life…”

Is that what drove my father to the extreme that he reached? Can dreams of beauty truly be born from nightmares of evil and midnight screams? Is the need to help others only a reflection of the need to help oneself? Is love only a way of sharing grief and pain?

I don’t know but, as long as I live, I will search for the answers. All I can do, all anyone can do, is to keep trying. For by trying we improve and by improving we come a little closer to perfection … and to answers.

Sometimes I think I almost know.

Almost.

It’s not easy to be a superman. Cathryn doesn’t understand that. She still thinks I can do anything.

If only she were right. Maybe she is. Perhaps a pound of cure doesn’t have to mean a pound of flesh. You have to live for today if you’re to live until To-morrow.

The Annie Bennett Memorial Vocational School for Young Women is almost finished.

Timeframe: Thursday, 29 June 1939 to Friday, 30 June 1939

Word Count: ~13,000 words

This work is copyright © 2011–2015 by Cainnech Roberson, all rights reserved.

Please don’t repost this document or make this document publicly accessible via FTP, mail server or archive site without explicit permission.

Permission is granted for one hard copy for personal use.

Last Update: 25 August 2018